‘Young Women Define Culture’: ReThinking The Role Of Fangirl For 2026

During an interview in November last year with NME, lead singer of Australian boyband 5 Seconds of Summer Luke Hemmings said ‘Young women define culture. They tell you what’s cool.’

Young women do define culture. They drive artist success, control genre popularity, and act as musicians’ most favourable PR teams – or their most damaging adversaries. In 2026, we must stop belittling fangirls and fan communities as nothing more than manipulatable pawns, and acknowledge their very real power and influence over the music industry.

The Groove is keen to do just that. For our first article of the year, we’re spotlighting fans.

Use of the term ‘fangirl’ picked up around twenty years ago. Google ‘what is a fangirl?’ now, and here’s what you’ll find (accurate as of January 2026).

‘(Noun.) a female fan, especially one who is obsessive about comics, film, music, or science fiction. (Verb.) (of a female fan) behave in an obsessive or overexcited way.’

There’s a thinly veiled sexism operating here. Google simply ‘what is a fan?’ and the response ditches the idea of intensity, or overbearing passion:

‘person who has a strong interest in or admiration for a particular person or thing’. ‘Football fans’ are given as an example.

‘But fangirls aren’t ‘normal’ fans, they scream their heads off, push their way to the front, take off their tops, and treat artists like they’re gods’, you say.

…Have you ever been to a football match?

This article isn’t exclusive to fangirls; rather, fan communities in general. However, it’s crucial to recognise this distinction, especially given the vital and largely uncredited role that young women specifically have historically played in popular music.

“In 2026, we must stop belittling fangirls and fan communities as nothing more than manipulatable pawns, and acknowledge their very real power and influence over the music industry.”

Fangirls (and fanboys) aren’t, by definition, ‘obsessive’ and ‘overexcited’. They’re the unwavering supporters you can count on to buy the gig tickets and albums, welcome musicians back into their lives like old friends after a career break or sonic shift, and stand by their chosen artist wanting nothing more than for them to succeed, perhaps one day to be noticed too. They’re unfortunately often exploited for it — with unethically priced meet and greets, a slew of poor quality merch, and never-ending ‘limited edition’ releases that prey on the scarcity mentality.

The Beatles, Elvis Presley and Michael Jackson are the obvious 20th century examples of legendary musicians. Guess who was standing front row at their early concerts, waiting for them outside hotels, and turning them from teenage daydreamers to the undisputed icons now constantly referenced in pop culture history?

As we head into the latter half of the 2020s, fan communities have planted firm roots online. On social media, most of us don’t follow our favourite artists’ bandmates, managers, producers, family members, record labels, and other fans – we just follow the individual or band. But artists are understandably more reserved with what they share, whether it’s celebratory, factual, or breaking bad news.

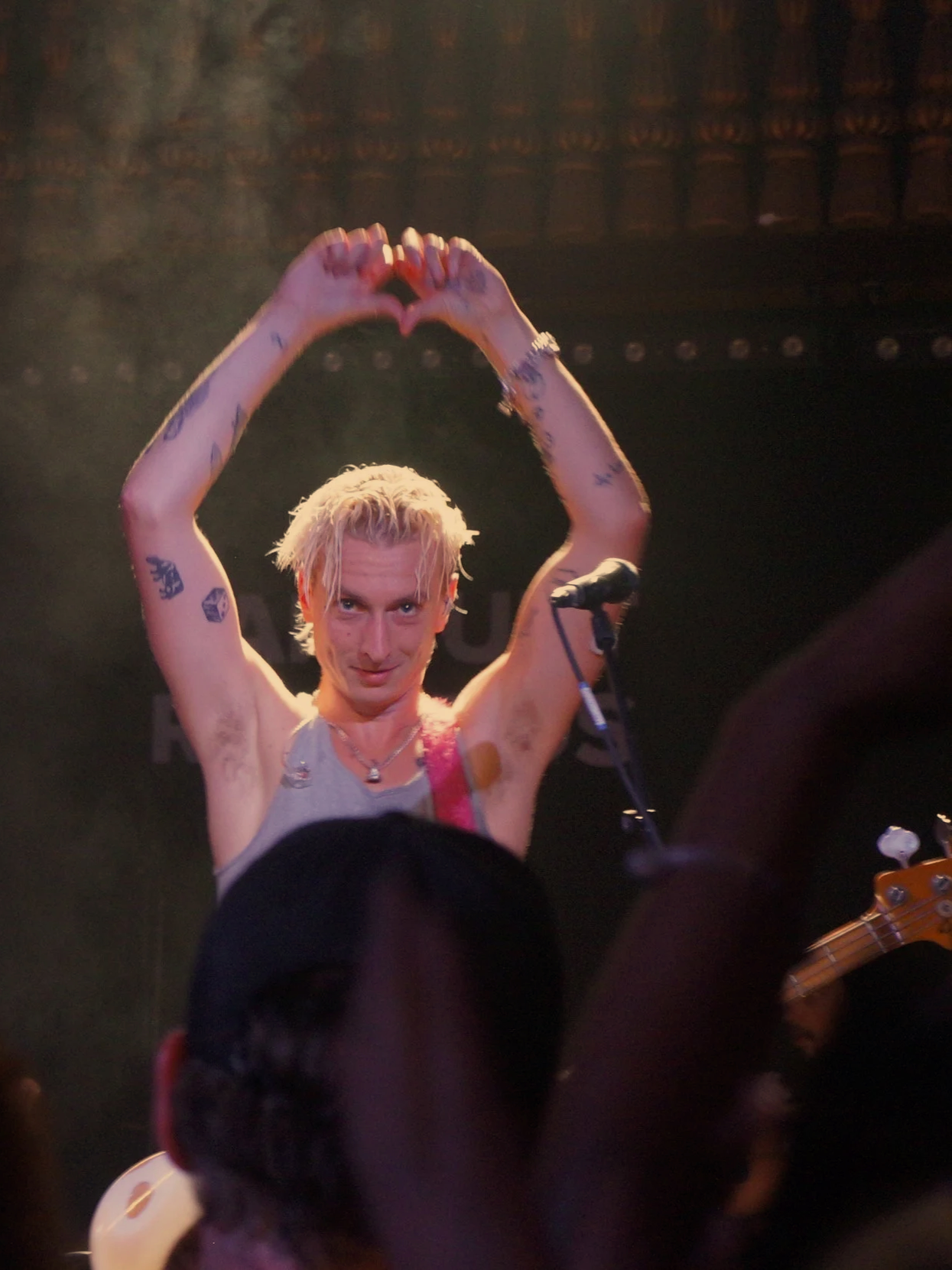

Filtering information through a fan account takes the heat (and the ego) off musicians, and many work more closely with their fan accounts than you might think – Yungblud, for example, has multiple Instagram verified fan accounts, with the largest at 2 million followers.

“Fan accounts... keep the conversation going. They grow an artist’s presence and relevancy from a grassroots level — the kind of authentic endorsement no PR campaign or budget can buy.”

Six-time BRIT winner RAYE even took to Twitter last year to say she uses the fan account ‘Raye Updates’ to track her own songs’ success. And don’t we all? Without realising, a lot of the content you consume regarding your favourite artists is probably via a fan account, whether it’s a collaboration with a photographer from a recent gig, condensed statements from an artist’s team or label, or tour and venue information centralised from a huge network of external sources.

These fan accounts are the ultimate hypepeople. They’re first to comment on an artists’ post, to reshare their good news, to defend unpopular moves such as cancelled shows or poorly reviewed music. Why wouldn’t you want your favourite artist to receive that level of loyalty?

Fan accounts are social media managers, full-time marketers, PR agents, newsrooms, and community hubs all wrapped into one. Whether sharing memes, photos, updates or opinion, they keep the conversation going. They grow an artist’s presence and relevancy from a grassroots level — the kind of authentic endorsement no PR campaign or budget can buy.

And they do it all at the risk of being labelled cringe, crazy and obsessed.

This isn’t defending fans who form parasocial relationships with their chosen musicians, publicly comment on artists’ personal lives, or, for want of a better word, stalk their artists from show to show and city to city. But it’s unfair and unwarranted to lump passionate fans into this minority, or reduce the definition of ‘fangirl’ to something inherently derogatory.

*

So here’s the thing: music doesn’t need to earn the approval of middle-aged men to be genuinely good.

In fact, fangirls are essential to many artist’s success. In 2026, they should be recognised by artists and their teams with humility, and treated with greater respect. Nor should they be sneered upon by ‘ordinary’ fans. Most of the time, they’re generating a community around the music you love, and actively rallying for the success of an artist you support.

And what is music made for, if not inspiring connection?